This article or section needs expansion.

An SSH key pair can be generated by running the ssh-keygen command, defaulting to 3072-bit RSA (and SHA256) which the ssh-keygen(1) man page says is 'generally considered sufficient' and should be compatible with virtually all clients and servers: $ ssh-keygen Generating public/private rsa key pair.

SSH keys can serve as a means of identifying yourself to an SSH server using public-key cryptography and challenge-response authentication. The major advantage of key-based authentication is that in contrast to password authentication it is not prone to brute-force attacks and you do not expose valid credentials, if the server has been compromised.[1]

Furthermore SSH key authentication can be more convenient than the more traditional password authentication. When used with a program known as an SSH agent, SSH keys can allow you to connect to a server, or multiple servers, without having to remember or enter your password for each system.

Key-based authentication is not without its drawbacks and may not be appropriate for all environments, but in many circumstances it can offer some strong advantages. A general understanding of how SSH keys work will help you decide how and when to use them to meet your needs.

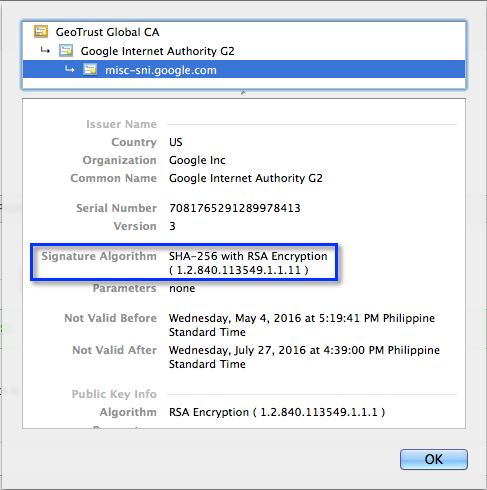

- If you’ve ever connected to a new server via SSH, you were probably greeted with a message about how the authenticity of the host couldn’t be established. The message and prompt looks something like this: The authenticity of host '1.2.3.4 (1.2.3.4)' can't be established. ECDSA key fingerprint is SHA256:nKYgfKJByTtMbnEAzAhuiQotMhL+t47Zm7bOwxN9j3g.

- The default is “sha256”.e This option will read a private or public OpenSSH key file and print to stdout a public key in one of the formats specified by the -m option. The default export format is “RFC4716”. This option allows exporting OpenSSH keys for use by other programs, including several commercial SSH implementations.

This article assumes you already have a basic understanding of the Secure Shell protocol and have installed the openssh package.

Background

SSH keys are always generated in pairs with one known as the private key and the other as the public key. The private key is known only to you and it should be safely guarded. By contrast, the public key can be shared freely with any SSH server to which you wish to connect.

If an SSH server has your public key on file and sees you requesting a connection, it uses your public key to construct and send you a challenge. This challenge is an encrypted message and it must be met with the appropriate response before the server will grant you access. What makes this coded message particularly secure is that it can only be understood by the private key holder. While the public key can be used to encrypt the message, it cannot be used to decrypt that very same message. Only you, the holder of the private key, will be able to correctly understand the challenge and produce the proper response.

This challenge-response phase happens behind the scenes and is invisible to the user. As long as you hold the private key, which is typically stored in the ~/.ssh/ directory, your SSH client should be able to reply with the appropriate response to the server.

A private key is a guarded secret and as such it is advisable to store it on disk in an encrypted form. When the encrypted private key is required, a passphrase must first be entered in order to decrypt it. While this might superficially appear as though you are providing a login password to the SSH server, the passphrase is only used to decrypt the private key on the local system. The passphrase is not transmitted over the network.

Generating an SSH key pair

An SSH key pair can be generated by running the ssh-keygen command, defaulting to 3072-bit RSA (and SHA256) which the ssh-keygen(1) man page says is 'generally considered sufficient' and should be compatible with virtually all clients and servers:

The randomart image was introduced in OpenSSH 5.1 as an easier means of visually identifying the key fingerprint.

-a switch to specify the number of KDF rounds on the password encryption.You can also add an optional comment field to the public key with the -C switch, to more easily identify it in places such as ~/.ssh/known_hosts, ~/.ssh/authorized_keys and ssh-add -L output. For example:

will add a comment saying which user created the key on which machine and when.

Choosing the authentication key type

OpenSSH supports several signing algorithms (for authentication keys) which can be divided in two groups depending on the mathematical properties they exploit:

- DSA and RSA, which rely on the practical difficulty of factoring the product of two large prime numbers,

- ECDSA and Ed25519, which rely on the elliptic curve discrete logarithm problem. (example)

Elliptic curve cryptography (ECC) algorithms are a more recent addition to public key cryptosystems. One of their main advantages is their ability to provide the same level of security with smaller keys, which makes for less computationally intensive operations (i.e. faster key creation, encryption and decryption) and reduced storage and transmission requirements.

OpenSSH 7.0 deprecated and disabled support for DSA keys due to discovered vulnerabilities, therefore the choice of cryptosystem lies within RSA or one of the two types of ECC.

#RSA keys will give you the greatest portability, while #Ed25519 will give you the best security but requires recent versions of client & server[2]. #ECDSA is likely more compatible than Ed25519 (though still less than RSA), but suspicions exist about its security (see below).

RSA

ssh-keygen defaults to RSA therefore there is no need to specify it with the -t option. It provides the best compatibility of all algorithms but requires the key size to be larger to provide sufficient security.

Minimum key size is 1024 bits, default is 3072 (see ssh-keygen(1)) and maximum is 16384.

If you wish to generate a stronger RSA key pair (e.g. to guard against cutting-edge or unknown attacks and more sophisticated attackers), simply specify the -b option with a higher bit value than the default:

Be aware though that there are diminishing returns in using longer keys.[3][4] The GnuPG FAQ reads: 'If you need more security than RSA-2048 offers, the way to go would be to switch to elliptical curve cryptography — not to continue using RSA.'[5]

On the other hand, the latest iteration of the NSA Fact Sheet Suite B Cryptography suggests a minimum 3072-bit modulus for RSA while '[preparing] for the upcoming quantum resistant algorithm transition'.[6]

ECDSA

The Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (ECDSA) was introduced as the preferred algorithm for authentication in OpenSSH 5.7. Some vendors also disable the required implementations due to potential patent issues.

Amtlib dll photoshop cc 2017. There are two sorts of concerns with it:

- Political concerns, the trustworthiness of NIST-produced curves being questioned after revelations that the NSA willingly inserts backdoors into softwares, hardware components and published standards were made; well-known cryptographers haveexpresseddoubts about how the NIST curves were designed, and voluntary tainting has already beenproved in the past.

- Technical concerns, about the difficulty to properly implement the standard and the slowness and design flaws which reduce security in insufficiently precautious implementations.

Both of those concerns are best summarized in libssh curve25519 introduction. Although the political concerns are still subject to debate, there is a clear consensus that #Ed25519 is technically superior and should therefore be preferred.

Ed25519

Ed25519 was introduced in OpenSSH 6.5 of January 2014: 'Ed25519 is an elliptic curve signature scheme that offers better security than ECDSA and DSA and good performance'. Its main strengths are its speed, its constant-time run time (and resistance against side-channel attacks), and its lack of nebulous hard-coded constants.[7] See also this blog post by a Mozilla developer on how it works.

It is already implemented in many applications and libraries and is the default key exchange algorithm (which is different from key signature) in OpenSSH.

Ed25519 key pairs can be generated with:

There is no need to set the key size, as all Ed25519 keys are 256 bits.

Keep in mind that older SSH clients and servers may not support these keys.

Choosing the key location and passphrase

Upon issuing the ssh-keygen command, you will be prompted for the desired name and location of your private key. By default, keys are stored in the ~/.ssh/ directory and named according to the type of encryption used. You are advised to accept the default name and location in order for later code examples in this article to work properly.

When prompted for a passphrase, choose something that will be hard to guess if you have the security of your private key in mind. A longer, more random password will generally be stronger and harder to crack should it fall into the wrong hands.

It is also possible to create your private key without a passphrase. While this can be convenient, you need to be aware of the associated risks. Without a passphrase, your private key will be stored on disk in an unencrypted form. Anyone who gains access to your private key file will then be able to assume your identity on any SSH server to which you connect using key-based authentication. Furthermore, without a passphrase, you must also trust the root user, as he can bypass file permissions and will be able to access your unencrypted private key file at any time.

Changing the private key's passphrase without changing the key

If the originally chosen SSH key passphrase is undesirable or must be changed, one can use the ssh-keygen command to change the passphrase without changing the actual key. This can also be used to change the password encoding format to the new standard.

Managing multiple keys

If you have multiple SSH identities, you can set different keys to be used for different hosts or remote users by using the Match and IdentityFile directives in your configuration:

See ssh_config(5) for full description of these options.

Storing SSH keys on hardware tokens

SSH keys can also be stored on a security token like a smart card or a USB token. This has the advantage that the private key is stored securely on the token instead of being stored on disk. When using a security token the sensitive private key is also never present in the RAM of the PC; the cryptographic operations are performed on the token itself. A cryptographic token has the additional advantage that it is not bound to a single computer; it can easily be removed from the computer and carried around to be used on other computers.

Examples are hardware tokens are described in:

- YubiKey#SSH notes Native OpenSSH support for FIDO/U2F keys

Copying the public key to the remote server

This article or section needs expansion.

Once you have generated a key pair, you will need to copy the public key to the remote server so that it will use SSH key authentication. The public key file shares the same name as the private key except that it is appended with a .pub extension. Note that the private key is not shared and remains on the local machine.

Simple method

sh shell such as tcsh as default and uses OpenSSH older than 6.6.1p1. See this bug report.If your key file is ~/.ssh/id_rsa.pub you can simply enter the following command.

If your username differs on remote machine, be sure to prepend the username followed by @ Ms2273 drivers. to the server name.

If your public key filename is anything other than the default of ~/.ssh/id_rsa.pub you will get an error stating /usr/bin/ssh-copy-id: ERROR: No identities found. In this case, you must explicitly provide the location of the public key.

If the ssh server is listening on a port other than default of 22, be sure to include it within the host argument.

Manual method

By default, for OpenSSH, the public key needs to be concatenated with ~/.ssh/authorized_keys. Begin by copying the public key to the remote server.

The above example copies the public key (id_ecdsa.pub) to your home directory on the remote server via scp. Do not forget to include the : at the end of the server address. Also note that the name of your public key may differ from the example given.

On the remote server, you will need to create the ~/.ssh directory if it does not yet exist and append your public key to the authorized_keys file.

The last two commands remove the public key file from the server and set the permissions on the authorized_keys file such that it is only readable and writable by you, the owner.

SSH agents

If your private key is encrypted with a passphrase, this passphrase must be entered every time you attempt to connect to an SSH server using public-key authentication. Each individual invocation of ssh or scp will need the passphrase in order to decrypt your private key before authentication can proceed.

An SSH agent is a program which caches your decrypted private keys and provides them to SSH client programs on your behalf. In this arrangement, you must only provide your passphrase once, when adding your private key to the agent's cache. This facility can be of great convenience when making frequent SSH connections.

An agent is typically configured to run automatically upon login and persist for the duration of your login session. A variety of agents, front-ends, and configurations exist to achieve this effect. This section provides an overview of a number of different solutions which can be adapted to meet your specific needs.

ssh-agent

ssh-agent is the default agent included with OpenSSH. It can be used directly or serve as the back-end to a few of the front-end solutions mentioned later in this section. When ssh-agent is run, it forks to background and prints necessary environment variables. E.g.

To make use of these variables, run the command through the eval command.

Once ssh-agent is running, you will need to add your private key to its cache:

If your private key is encrypted, ssh-add will prompt you to enter your passphrase. Once your private key has been successfully added to the agent you will be able to make SSH connections without having to enter your passphrase.

ssh clients, including git store keys in the agent on first use, add the configuration setting AddKeysToAgent yes to ~/.ssh/config. Other possible values are confirm, ask and no (default).In order to start the agent automatically and make sure that only one ssh-agent process runs at a time, add the following to your ~/.bashrc:

This will run a ssh-agent process if there is not one already, and save the output thereof. If there is one running already, we retrieve the cached ssh-agent output and evaluate it which will set the necessary environment variables. The lifetime of the unlocked keys is set to 1 hour.

There also exist a number of front-ends to ssh-agent and alternative agents described later in this section which avoid this problem.

Start ssh-agent with systemd user

It is possible to use the systemd/User facilities to start the agent. Use this if you would like your ssh agent to run when you are logged in, regardless of whether x is running.

Then export the environment variableSSH_AUTH_SOCK='$XDG_RUNTIME_DIR/ssh-agent.socket' in your login shell initialization file, such as ~/.bash_profile.

Finally, enable or start the service with the --user flag.

ssh-agent as a wrapper program

An alternative way to start ssh-agent (with, say, each X session) is described in this ssh-agent tutorial by UC Berkeley Labs. A basic use case is if you normally begin X with the startx command, you can instead prefix it with ssh-agent like so:

And so you do not even need to think about it you can put an alias in your .bash_aliases file or equivalent:

Doing it this way avoids the problem of having extraneous ssh-agent instances floating around between login sessions. Exactly one instance will live and die with the entire X session.

ssh-agent startx, you can add eval $(ssh-agent) to ~/.xinitrc.See the below notes on using x11-ssh-askpass with ssh-add for an idea on how to immediately add your key to the agent.

GnuPG Agent

The gpg-agent has OpenSSH agent emulation. See GnuPG#SSH agent for necessary configuration.

Keychain

Keychain is a program designed to help you easily manage your SSH keys with minimal user interaction. It is implemented as a shell script which drives both ssh-agent and ssh-add. A notable feature of Keychain is that it can maintain a single ssh-agent process across multiple login sessions. This means that you only need to enter your passphrase once each time your local machine is booted.

Installation

Install the keychain package.

Configuration

-Q, --quick option has the unexpected side-effect of making keychain switch to a newly-spawned ssh-agent upon relogin (at least on systems using GNOME), forcing you to re-add all the previously registered keys.Add a line similar to the following to your shell configuration file, e.g. if using Bash:

~/.bashrc is used instead of the upstream suggested ~/.bash_profile because on Arch it is sourced by both login and non-login shells, making it suitable for textual and graphical environments alike. See Bash#Invocation for more information on the difference between those.In the above example,

- the

--evalswitch outputs lines to be evaluated by the openingevalcommand; this sets the necessary environment variables for an SSH client to be able to find your agent. --quietwill limit output to warnings, errors, and user prompts.

Multiple keys can be specified on the command line, as shown in the example. By default keychain will look for key pairs in the ~/.ssh/ directory, but absolute path can be used for keys in non-standard location. You may also use the --confhost option to inform keychain to look in ~/.ssh/config for IdentityFile settings defined for particular hosts, and use these paths to locate keys.

Ssh Show Sha256 Fingerprint

See keychain --help or keychain(1) for details on setting keychain for other shells.

To test Keychain, simply open a new terminal emulator or log out and back in your session. It should prompt you for the passphrase of the specified private key(s) (if applicable), either using the program set in $SSH_ASKPASS or on the terminal.

Because Keychain reuses the same ssh-agent process on successive logins, you should not have to enter your passphrase the next time you log in or open a new terminal. You will only be prompted for your passphrase once each time the machine is rebooted.

Tips

- keychain expects public key files to exist in the same directory as their private counterparts, with a

.pubextension. If the private key is a symlink, the public key can be found alongside the symlink or in the same directory as the symlink target (this capability requires thereadlinkcommand to be available on the system).

- to disable the graphical prompt and always enter your passphrase on the terminal, use the

--noguioption. This allows to copy-paste long passphrases from a password manager for example.

- if you do not want to be immediately prompted for unlocking the keys but rather wait until they are needed, use the

--noaskoption.

--agents option, e.g.--agents ssh,gpg. See keychain(1).x11-ssh-askpass

The x11-ssh-askpass package provides a graphical dialog for entering your passhrase when running an X session. x11-ssh-askpass depends only on the libx11 and libxt libraries, and the appearance of x11-ssh-askpass is customizable. While it can be invoked by the ssh-add program, which will then load your decrypted keys into ssh-agent, the following instructions will, instead, configure x11-ssh-askpass to be invoked by the aforementioned Keychain script.

Install the keychain and x11-ssh-askpass packages.

Edit your ~/.xinitrc file to include the following lines, replacing the name and location of your private key if necessary. Be sure to place these commands before the line which invokes your window manager.

In the above example, the first line invokes keychain and passes the name and location of your private key. If this is not the first time keychain was invoked, the following two lines load the contents of $HOSTNAME-sh and $HOSTNAME-sh-gpg, if they exist. These files store the environment variables of the previous instance of keychain.

Calling x11-ssh-askpass with ssh-add

The ssh-add manual page specifies that, in addition to needing the DISPLAY variable defined, you also need SSH_ASKPASS set to the name of your askpass program (in this case x11-ssh-askpass). It bears keeping in mind that the default Arch Linux installation places the x11-ssh-askpass binary in /usr/lib/ssh/, which will not be in most people's PATH. This is a little annoying, not only when declaring the SSH_ASKPASS variable, but also when theming. You have to specify the full path everywhere. Both inconveniences can be solved simultaneously by symlinking:

This is assuming that ~/bin is in your PATH. So now in your .xinitrc, before calling your window manager, one just needs to export the SSH_ASKPASS environment variable:

and your X resources will contain something like:

Doing it this way works well with the above method on using ssh-agent as a wrapper program. You start X with ssh-agent startx and then add ssh-add to your window manager's list of start-up programs.

Theming

The appearance of the x11-ssh-askpass dialog can be customized by setting its associated X resources. Some examples are the .ad files at https://github.com/sigmavirus24/x11-ssh-askpass. See x11-ssh-askpass(1) for full details.

Alternative passphrase dialogs

There are other passphrase dialog programs which can be used instead of x11-ssh-askpass. The following list provides some alternative solutions.

- ksshaskpass uses the KDE Wallet.

- openssh-askpass uses the Qt library.

pam_ssh

The pam_ssh project exists to provide a Pluggable Authentication Module (PAM) for SSH private keys. This module can provide single sign-on behavior for your SSH connections. On login, your SSH private key passphrase can be entered in place of, or in addition to, your traditional system password. Once you have been authenticated, the pam_ssh module spawns ssh-agent to store your decrypted private key for the duration of the session.

To enable single sign-on behavior at the tty login prompt, install the unofficial pam_sshAUR package.

~/.ssh/login-keys.d/.Create a symlink to your private key file and place it in ~/.ssh/login-keys.d/. Replace the id_rsa in the example below with the name of your own private key file.

Edit the /etc/pam.d/login configuration file to include the text highlighted in bold in the example below. The order in which these lines appear is significiant and can affect login behavior.

In the above example, login authentication initially proceeds as it normally would, with the user being prompted to enter his user password. The additional auth authentication rule added to the end of the authentication stack then instructs the pam_ssh module to try to decrypt any private keys found in the ~/.ssh/login-keys.d directory. The try_first_pass option is passed to the pam_ssh module, instructing it to first try to decrypt any SSH private keys using the previously entered user password. If the user's private key passphrase and user password are the same, this should succeed and the user will not be prompted to enter the same password twice. In the case where the user's private key passphrase user password differ, the pam_ssh module will prompt the user to enter the SSH passphrase after the user password has been entered. The optional control value ensures that users without an SSH private key are still able to log in. In this way, the use of pam_ssh will be transparent to users without an SSH private key.

If you use another means of logging in, such as an X11 display manager like SLiM or XDM and you would like it to provide similar functionality, you must edit its associated PAM configuration file in a similar fashion. Packages providing support for PAM typically place a default configuration file in the /etc/pam.d/ directory.

Further details on how to use pam_ssh and a list of its options can be found in the pam_ssh(8) man page.

Using a different password to unlock the SSH key

If you want to unlock the SSH keys or not depending on whether you use your key's passphrase or the (different!) login password, you can modify /etc/pam.d/system-auth to

For an explanation, see [8].

Known issues with pam_ssh

Work on the pam_ssh project is infrequent and the documentation provided is sparse. You should be aware of some of its limitations which are not mentioned in the package itself.

- Versions of pam_ssh prior to version 2.0 do not support SSH keys employing the newer option of ECDSA (elliptic curve) cryptography. If you are using earlier versions of pam_ssh you must use either RSA or DSA keys.

- The

ssh-agentprocess spawned by pam_ssh does not persist between user logins. If you like to keep a GNU Screen session active between logins you may notice when reattaching to your screen session that it can no longer communicate with ssh-agent. This is because the GNU Screen environment and those of its children will still reference the instance of ssh-agent which existed when GNU Screen was invoked but was subsequently killed in a previous logout. The Keychain front-end avoids this problem by keeping the ssh-agent process alive between logins.

pam_exec-ssh

As an alternative to pam_ssh you can use pam_exec-sshAUR. It is a shell script that uses pam_exec. Help for configuration can be found upstream.

GNOME Keyring

If you use the GNOME desktop, the GNOME Keyring tool can be used as an SSH agent. See the GNOME Keyring article for further details.

Store SSH keys with Kwallet

For instructions on how to use kwallet to store your SSH keys, see KDE Wallet#Using the KDE Wallet to store ssh key passphrases.

KeePass2 with KeeAgent plugin

KeeAgent is a plugin for KeePass that allows SSH keys stored in a KeePass database to be used for SSH authentication by other programs.

- Supports both PuTTY and OpenSSH private key formats.

- Works with native SSH agent on Linux/Mac and with PuTTY on Windows.

See KeePass#Plugin installation in KeePass or install the keepass-plugin-keeagent package.

This agent can be used directly, by matching KeeAgent socket: KeePass -> Tools -> Options -> KeeAgent -> Agent mode socket file -> %XDG_RUNTIME_DIR%/keeagent.socket-and environment variable:export SSH_AUTH_SOCK='$XDG_RUNTIME_DIR'/keeagent.socket'.

KeePassXC

The KeePassXC fork of KeePass supports being used as an SSH agent by default. It is also compatible with KeeAgent's database format.

Troubleshooting

Key ignored by the server

- If it appears that the SSH server is ignoring your keys, ensure that you have the proper permissions set on all relevant files.

- For the local machine:

- For the remote machine:

- For the remote machine, also check that the target user's home directory has the correct permissions (it must not be writable by the group and others):

- If that does not solve the problem you may try temporarily setting

StrictModestonoin/etc/ssh/sshd_config. If authentication withStrictModes offis successful, it is likely an issue with file permissions persists.

- Make sure keys in

~/.ssh/authorized_keysare entered correctly and only use one single line. - Make sure the remote machine supports the type of keys you are using: some servers do not support ECDSA keys, try using RSA or DSA keys instead, see #Generating an SSH key pair.

- You may want to use debug mode and monitor the output while connecting:

- If you gave another name to your key, for example

id_rsa_server, you need to connect with the-ioption:

See also

- OpenSSH key management: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3

Cisco Ssh Sha256

The Secure Hash Algorithms are a family of cryptographic hash functions published by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) as a U.S.Federal Information Processing Standard (FIPS), including:

- SHA-0: A retronym applied to the original version of the 160-bit hash function published in 1993 under the name 'SHA'. It was withdrawn shortly after publication due to an undisclosed 'significant flaw' and replaced by the slightly revised version SHA-1.

- SHA-1: A 160-bit hash function which resembles the earlier MD5 algorithm. This was designed by the National Security Agency (NSA) to be part of the Digital Signature Algorithm. Cryptographic weaknesses were discovered in SHA-1, and the standard was no longer approved for most cryptographic uses after 2010.

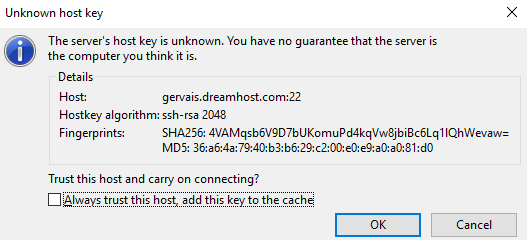

- SHA-2: A family of two similar hash functions, with different block sizes, known as SHA-256 and SHA-512. They differ in the word size; SHA-256 uses 32-byte words where SHA-512 uses 64-byte words. There are also truncated versions of each standard, known as SHA-224, SHA-384, SHA-512/224 and SHA-512/256. These were also designed by the NSA.

- SHA-3: A hash function formerly called Keccak, chosen in 2012 after a public competition among non-NSA designers. It supports the same hash lengths as SHA-2, and its internal structure differs significantly from the rest of the SHA family.

The corresponding standards are FIPS PUB 180 (original SHA), FIPS PUB 180-1 (SHA-1), FIPS PUB 180-2 (SHA-1, SHA-256, SHA-384, and SHA-512). NIST has updated Draft FIPS Publication 202, SHA-3 Standard separate from the Secure Hash Standard (SHS).

Comparison of SHA functions[edit]

Ssh Sha256

In the table below, internal state means the 'internal hash sum' after each compression of a data block.

| Algorithm and variant | Output size (bits) | Internal state size (bits) | Block size (bits) | Rounds | Operations | Security against collision attacks (bits) | Security against length extension attacks (bits) | Performance on Skylake (median cpb)[1] | First published | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long messages | 8 bytes | ||||||||||

| MD5 (as reference) | 128 | 128 (4 × 32) | 512 | 64 | And, Xor, Rot, Add (mod 232), Or | ≤ 18 (collisions found)[2] | 0 | 4.99 | 55.00 | 1992 | |

| SHA-0 | 160 | 160 (5 × 32) | 512 | 80 | And, Xor, Rot, Add (mod 232), Or | < 34 (collisions found) | 0 | ≈ SHA-1 | ≈ SHA-1 | 1993 | |

| SHA-1 | < 63 (collisions found)[3] | 3.47 | 52.00 | 1995 | |||||||

| SHA-2 | SHA-224 SHA-256 | 224 256 | 256 (8 × 32) | 512 | 64 | And, Xor, Rot, Add (mod 232), Or, Shr | 112 128 | 32 0 | 7.62 7.63 | 84.50 85.25 | 2004 2001 |

| SHA-384 SHA-512 | 384 512 | 512 (8 × 64) | 1024 | 80 | And, Xor, Rot, Add (mod 264), Or, Shr | 192 256 | 128 (≤ 384) 0[4] | 5.12 5.06 | 135.75 135.50 | 2001 | |

| SHA-512/224 SHA-512/256 | 224 256 | 112 128 | 288 256 | ≈ SHA-384 | ≈ SHA-384 | 2012 | |||||

| SHA-3 | SHA3-224 SHA3-256 SHA3-384 SHA3-512 | 224 256 384 512 | 1600 (5 × 5 × 64) | 1152 1088 832 576 | 24[5] | And, Xor, Rot, Not | 112 128 192 256 | 448 512 768 1024 | 8.12 8.59 11.06 15.88 | 154.25 155.50 164.00 164.00 | 2015 |

| SHAKE128 SHAKE256 | d (arbitrary) d (arbitrary) | 1344 1088 | min(d/2, 128) min(d/2, 256) | 256 512 | 7.08 8.59 | 155.25 155.50 | |||||

Validation[edit]

All SHA-family algorithms, as FIPS-approved security functions, are subject to official validation by the CMVP (Cryptographic Module Validation Program), a joint program run by the American National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the Canadian Communications Security Establishment (CSE).

Sha256 Ssh-keygen

References[edit]

Ssh Sha256 Fingerprint

- ^'Measurements table'. bench.cr.yp.to.

- ^Tao, Xie; Liu, Fanbao; Feng, Dengguo (2013). Fast Collision Attack on MD5(PDF). Cryptology ePrint Archive (Technical report). IACR.

- ^Stevens, Marc; Bursztein, Elie; Karpman, Pierre; Albertini, Ange; Markov, Yarik. The first collision for full SHA-1(PDF) (Technical report). Google Research. Lay summary – Google Security Blog (February 23, 2017).

- ^Without truncation, the full internal state of the hash function is known, regardless of collision resistance. If the output is truncated, the removed part of the state must be searched for and found before the hash function can be resumed, allowing the attack to proceed.

- ^'The Keccak sponge function family'. Retrieved 2016-01-27.